On 22 August 1665, Samuel Pepys stumbled across an open coffin in a close near Greenwich and was shocked ‘the parish hath not appointed anybody to bury it but only set a watch there day and night, that nobody should go thither or come thence’. Burial increasingly presented a logistical and spatial challenge for London’s parishes as the population expanded exponentially from the mid-sixteenth century. Accommodating vast numbers of plague dead in an epidemic year presented the potential for administrative collapse, particularly in the suburban and outer-parishes where mortality was elevated several times above normal levels and might generate thousands of additional burials. In Gods Tokens, of His fearefull Iudgements, Thomas Dekker dramatically referred to ‘many Church-yards (for want of roome)’ compelled to ‘dig Graues like little Cellers, piling vp forty or fifty in a Pit’ during the epidemic of 1625.

Over a million deaths occurred in London between 1550 and 1666, with between ten and fifteen thousand burials every year. Parishes used fees, careful planning of grave location and knowledge of past interments, bone removal and disturbance and sought additional burial ground to control and conserve space in non-plague years. Plague naturally placed immense and concentrated pressure on burial space. Vanessa Harding revealed parishes approaching this burden pragmatically, following standard methods of conservation and control for as long as possible, society deriving strength from observing what it saw as its ‘own traditions’ in time of crisis. Only when inadequate did vestries resort to common burial, ‘a shocking breech of custom, an offence to dignity’ but accepted by contemporaries as necessary during a plague epidemic.

Fig 1. Burial of plague dead in open pits in 1665.

Harding referred to the ‘mythology’ of the plague pit in London, and suggested the overall number may have been limited and confined to the suburbs, the smaller city-centre parishes not needing to implement this ‘desperate expedient’. Parish records give weight to this view, the most common reference to pits located in the records of the suburban parishes. Harding also suggested mass graves may have been used by parishes to save money, certainly plausible for the larger suburban parishes under immense financial pressure but also with better opportunities to acquire new grounds. The stark reality in 1665 was that many suburban parishes were required to find space for several thousand more bodies than a non-plague year. Open pits meant this could be achieved quickly and cheaply.

The burden of disposing of the dead and available resources were unevenly spread across the city and metropolitan environs. Paul Slack described the burial spaces in many suburban parishes in later epidemics, ‘soon overflowing’ and their officials ‘overwhelmed’, and pondered the ‘psychological and administrative burden’ of having to accommodate so many dead. Slack extended the problems of burial to the intramural parishes, not completely insulated, their graveyards ‘literally piled high with corpses’ in 1665. In her analysis of St Bride Fleet Street’s burial of plague dead through 1665, Harding argued the parish struggling under the pressure of events but was not overwhelmed. The records for other suburban parishes reflect this pressure and tend to support Harding’s argument.

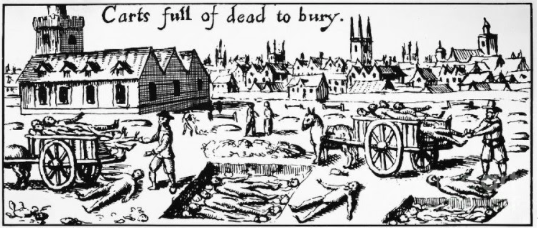

Fig 2. The four ‘extramural’ or inner suburban parishes used in this study.

Daniel Defoe, in his fictional account of London’s epidemic in 1665, provided a sobering account of the scale of the burial problem in 1665. His protagonist lamented the number of poor ‘carried away in the Dead-Carts’ and ‘thrown into the common Graves of every parish’, normal practice breaking down and parishes forced to adopt common burial. He reported his parish, the easterly inner suburban parish of St Botolph Aldgate, having dug a ‘great Pit in the Church-Yard’, a ‘terrible Pit’. Defoe reports it being about ’40 Foot in Length, and about 15 or 16 Foot broad’, initially to a depth of ‘nine Foot’, and eventually extending to ’20 Foot deep’. Apparently ‘several large Pits’ had been dug before this. The parish accounts show payments for ‘earth for the churchyard’, ‘diggings of pitts in the Contagious Sickne tyme’, and later in the epidemic, ‘more Earth for the churchyard & for labours’. An interesting reference to the purchase of ‘16 yardes of cloth’ possibly relates to a move from coffined to shrouded burial, a money and space-saving expedient.

Defoe reports the churchwardens at St Botolph Aldgate believing the aforementioned pit, dug on 6 September, ‘would have supply’d a Month or more’. By 20 September, the parish was ‘obliged to fill it up’, due to the 1,114 bodies that had been ‘thrown into it’ over the two weeks. Parishioners displayed their aversion to mass burial when telling the churchwardens they were ‘making Preparations to bury the whole Parish’. Defoe also mentions pits in Finsbury and Cripplegate, ‘lying open then in the Fields’ and not ‘wall’d about’, and others in ‘several Church-yards, or burying Grounds’. The measure was widespread and a common resort for many parishes, ‘if not all the out parishes’. Defoe’s overall perception though is parishes coping, his definition; ‘no dead Bodies remain’d unburied’ and none for ‘want of People to carry them off’, nor ‘Buriers to put them into the Ground’. Although stretched immensely, he argued London was able to accommodate its dead, reports in the aftermath of the epidemic that the ‘Dead lay unburied’, ‘utterly false’. Defoe’s account, lucid and entertaining as it is and based on primary sources and no doubt witness testimony, is fiction. Parish records though, provide an equally sobering picture of the terrible burial burden an efforts to meet the challenge.

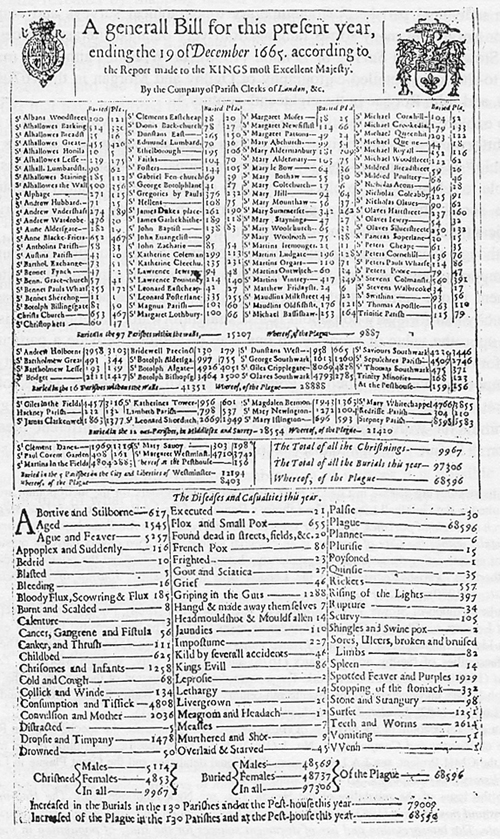

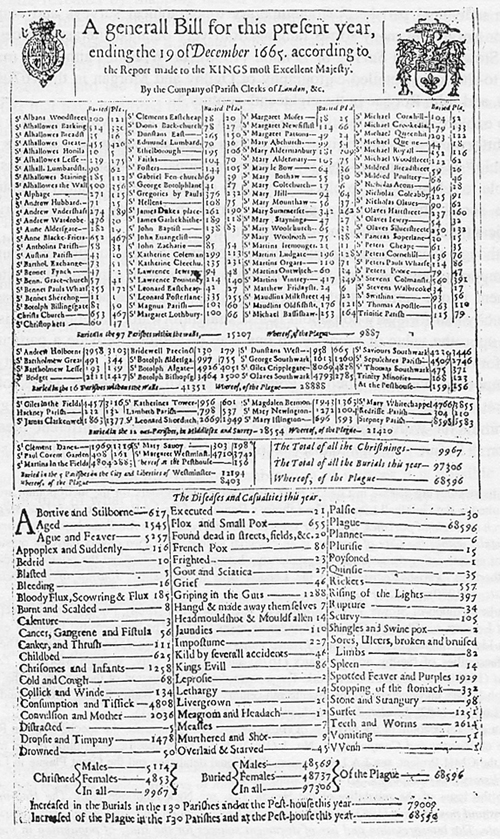

Fig 3. A ‘generall Bill’ showing total burials and plague burials for parishes across the wider metropolitan environs of London in 1665. Daniel Defoe suggested the actual number of plague deaths was closer to 100,000.

Of the nearly 3,500 deaths recorded in 1665 in the north-easterly inner suburban parish of St Botolph Bishopsgate, 2500 were attributed to plague. On 8 August, the vestry voted the ‘wast Ground betwixt Mr Valentines’ house and the almshouses be ‘enclosed for a burial place’. Their ground was ‘so full of corps’, that place was ‘now wanting to bury the Dead’. It was at the ‘Churchwardens discretion to do it to the best advantage of the parish’. No burials were recorded between 26 June and 1 January, indicative of the pressure the vestry was under and the pressing need to secure space. On 6 September, the vestry voted the large ‘shed in petiframe’ be ‘pulled downe and the ground to be Digd and brought into the lower church yard’, the churchyard ‘being fild so full with corps that there is noe room left to buryie the dead’. The parish was unsurprisingly struggling to accommodate vastly increased numbers of dead than in a non-plague year. The vestry though, appeared a functioning and effective unit, their decisions responsive to the crisis as it evolved, and seemingly quite proactive. With their space close to full and it only being early August, they sensibly looked to create new burial ground on wasteland. When even this was insufficient, they reworked older space by raising the level of the churchyard to accommodate more burials. Defoe considered this measure common in the out-parishes with the ‘prodigious Numbers of People’ who died ‘in so short a Space of Time’.

The westerly inner suburban parish of St Bride Fleet Street exhibited a similar control and conserve response to burial in 1665. As early as 16 June, the vestry had ordered burials from St Martins Ludgate be charged double duties, ‘because our ground begin to fill’. On 3 July, the sexton was ‘incouraged to dig the graues deeper’. He was to ‘receive something extraordinary for his pains’. Restriction on church burial followed on 7 July with an order that ‘none whatsoever shalbe buryed in the church’, exceptions made though ‘for such that have office of the Parish by service’, and those that ‘paid 3& a weeke to the poore’. Even these would only be accepted in the ‘upper churchyard & none other’. Normal burial practice, adhered to as long as possible, was replaced with common burial by 26 August, two labourers paid for ‘6 days of work digging a pitt’, and ‘more to 5 labourors for 4 days’. Additional payments were disbursed for ‘digging in ye pitt’ on October 14, and to ‘Edward Reynolds for labours in the backe churchyard’ four days later.

St Giles Cripplegate consistently carried the greatest number of total plague dead in epidemics through the period. The northerly inner suburban parish reported 8,069 burials in 1665, a staggering 4,838 of these attributed to plague. The yearly average between 1657 and 1664 was 1,126, leaving the parish with almost 7,000 more burials to accommodate in 1665, an unfathomable concentration of mortality. Cumulative issues of burial space had emerged at St Giles Cripplegate as early as mid-1664 and reflect the ongoing population growth of the parish through the seventeenth-century. On 4 June, the vestry ‘Agreed, that there shall be no more corpses buried in Whitecross-street churchyard, under the penalty of the payment of three pounds to the Vicar and the rest of the Vestrymen’, until ‘ten years are expired’. With a lack of space apparent in a non-plague year, the likelihood of the parish faring well in 1665 appeared slim indeed.

Defoe reported the plague thickening across ‘Cripplegate Parish’ through late July of 1665, ‘eight hundred eighty six’ buried in the second week of August alone. The disease began to abate slightly in the parish through the beginning of September as it moved further east and into the City itself. Even so, 456 burials were recorded in the week beginning 12 September, decreasing to 277 in the week beginning 19 September, and 196 for that of 26 September. By late September 1665, the vestry was forced to act. They ordered the churchwardens to ‘forthwith raise the Lower churchyard…two foote higher with earth’, and ‘not any person be allowed to be buried under a pew in the churche, unless the parties concerned doe at their own proper costs and charges lay down the same again’. By the end of September, burial space was exhausted. The accounts show payments to Mr Johnson and Alliston for bringing 1,196 loads of earth into the lower churchyard and labourers paid for ‘spreading it at several times’.

Although standard burial practice must have long since passed, the parish did accommodate all those who fell of plague, and other causes of death, through 1665. The cumulative impact of the epidemic was felt well into and beyond 1666. On 16 January 1666, the vestry reported the ‘churchyards and burying places are now almost filled with dead corpses’, and ‘that not any more can scarcely be buried’; their remedy, therefore, that ‘we may have more ground’. Members of the vestry were appointed to a committee to ‘treat for the purchase of houses and grounds in Churchyard Alley adjoining the Church’. In October, the churchwardens were asked to report to the next vestry ‘how much ground in the alley by Crowden’s Well’ was out of a lease, and could potentially be added to the lower churchyard. While the new ground was sought, the vestry implemented further restrictions on their space, ordering on 23 January 1667, that ‘no person shall be buried in the Upper Churchyard or burying-place by the Pest House’ for seven years. The Bishop of Rochester, acting under a commission from the Bishop of London, consecrated ground south of the church on 9 October 1667. Spatial pressures persisted. The population displacement caused by the Great Fire likely compounded burial issues for the parish as the parochial population swelled. A vestry order from January 1668 extended the restriction on burial in the upper churchyard and place by the pest house to the ‘Lower or old churchyard’. As late as 1672, the vestry was forced to decree coffined burials ‘shall pay the full dues of burial’, but any choosing to be buried ‘in a sheet only’ would have the fees remitted.

As early as August 1665, Guildhall was concerned with the fullness of ‘sundry’ churchyards, including the common burial ground at the New Churchyard, established in 1569. Sir John Robinson was to ‘treat’ with one Mr. Tindall, the City’s tenant at Finsbury Fields, to allocate a new area for burial. The fullness of both the New Churchyard and that at Bethlehem was also behind the move to look to Bunhill Fields for burial space. The situation only worsened and in October the Court of Aldermen was receiving complaints at the stench from the New Churchyard and ordered that no more bodies were to be interred in pits there. An instruction was issued to lay fresh mould to speed up decomposition and find what space they could for single burials. Later that month, the bricklayer John Tanor was paid for erecting a wall about the ‘new burying place’ in Finsbury Fields. Whilst the City endeavoured to address the lack of space in non-parochial grounds, responsibility for burial was mostly placed at the individual parish level. Parish’s were viewed as the nexus of plague-time activity, and in that light, burial was simply another challenge, alongside those of quarantining infected houses and supporting the poor infected, that suburban and outer parishes were required to meet.

Vanessa Harding emphasised parishes having to define their priorities and ‘adopt strategies to cope’ with growing pressure on their burial space through the seventeenth-century. This was amplified during a plague epidemic. The records of several inner suburban parishes demonstrate the scale of the problem facing parishes in the suburban and outer environs of London but also the pragmatic approach they worked to in meeting the challenge of accommodating plague dead.

By Aaron Columbus

Sources:

Primary:

LMA ms.9235/1-2: CA 1547-1691, ff.431-432 / ms.9237: CA 1622-1678, 1665, St Botolph Aldgate Churchwardens’ Accounts.

LMA ms.4526/1: VM 1616-1690, ff.126 – St Botolph Bishopsgate Vestry Minutes.

LMA ms.6552/1: CA 1639-78, 26 August & 14/18 October 1665, St Bride Fleet Street Churchwardens’ Accounts.

LMA Repertories, 109/194.

Printed primary:

Daniel Defoe, Journal of a Plague Year (London: Penguin, 2003), 34, 59, 179, 222.

William Denton, Records of St Giles Cripplegate (London: Bell and Sons, 1883), 127.

Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys (London: Penguin, 2003), 201.

Frank Wilson (ed), Dekkers Plague Pamphlets (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925), 159.

Secondary:

Vanessa Harding, ‘And one more may be laid there’: the Location of Burials in Early Modern London’, London Journal 14, 1989, 112.

Vanessa Harding, The Dead and Living in Paris and London (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 272.

Vanessa Harding, ’Burial of the plague dead in early modern London’, J.A.I. Champion (ed.), Epidemic Disease in London (Centre for Metropolitan History Working Papers Series, No. 1, 1993), 59.

Paul Slack, ‘Metropolitan government in crisis: the response to plague’, in A.L.Beier and R. Finlay (eds.), The Making of the Metropolis: London 1500-1700, (London : Longman, 1986), 64.